Aland 2008 on the BIACS3 Bienale in Sevillia/Granada

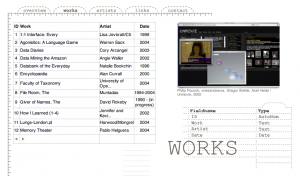

The title of our current collaborative installation at BIACS3 Seville Biannual, Aland, is an abbreviation for Al-Andalus, celebrating the exhibition site’s unique moment of cultural and religious conviviality a millenium ago. Aland is also ‘a land’, a Deleuzian ‘any place whatever‘, such as the consensual space of cyber-documentary pictures of contemporary Andalusians from which Aland draws the bulk of its visual content, montaged, more precisely, ‘mashed up’ over 22 repaired or recycled flatscreens and 68 brilliant, hi-res OLED Organic mini displays.

Aland consists of 3 interactive and interacting sculptures, portraits if you will of a Modern, Muslim, Jewish historically acclaimed literary figures, Fedrico García Lorca, Muhammad Ibn Tufail and Moses Maimonides. They interact by simulating a conversation, exchanging dialogue composed by algorithmical linguistics, consciously dadaistic in character, yet subconsciously, subtextually retaining an uncanny verisimilitude to each interlocutor. The Lorca-presenting character draws its replies from translations of his poetry; the Ibn Tufail digital mimic recombines into workable sentences phrases from his 11th C. philosophical novel Alive, Son of Awake; and Moses II as Maimonides is often nicknamed, playfully revises the rigorous logic in his Guide for the Perplexed.

It is the vocabulary uttered by these 3 so-called Chatbots that links their never-ending verbal exchange with pools of Andalusian user images that have been tagged by descriptive words online. The main screen in each sculpture is fed by these stream of visual consciousness pictures, arrayed in a freestyle mosaical manner. Visually scripted to reduce size on-the-fly, these picture streams become fair game for batteries of webcam-modified birdwatching scopes and various optical instruments surveilling close-ups and details of their visual presence on their respective target screen. It is not an individual but their image, not a person in public space but a screen space that is surveilled. These digital monoculars and spyglasses are scripted to capture screen images and feed them into vast pools of Andalusian cyberdocumentary pictures, on the look out for similar pictures. Pictures look at pictures according to pattern, light and color. Each pictures content diverges to generate implied narrative natural to the contents’ cohesive context, Andalusia, while being informatically abstract. According to scripted levels of picture similarity, numerous playlists of pictures are displayed rhythmically on numerous screens in real time in the installation.

The public interacts by sending any image to a sculpture via their cellphone camera or storage locally via Bluetooth, by mobile- and e-mail to alander@zkm.de, by upload from the aland website, or locally again by two webcams adorning the Moses and Federico sculptures, namely, the SmileCam which locates biannual visitors faces, zooms in, and if a smiling expression is identified, a picture is taken and fed into the database to generate its movie clip mash up of similar cyber-Andalusians; the other, Linecam, only records single pixel width lines of persons before its lens over time, its morphed slices of visitor-time scripted to capture and send at intervals an image to the database and screen its resulting mashup.

The 6 scripted Linux computers themselves form the bodies of the 3 sculptures. Lorca’s computer housings have been sculpted and worked as a birdhouse on which are perched 2 bronze figures Pointer and Sitter, and draped with a discreet grey silicon mandala. Muhammad has 4 supporting tripods piercing through its working computers, only centimeters from his motherboards. Adjunct to this are 3 tripods supporting a telescope, model fruit tree and screen, Gardencam, which uses visual feedback and subtle scripting to reproduce live the magnified model tree on screen in some magical weather conditions. Moses body is perched across the upper rungs of a tall ladder. Atop his Mooncam, a vignetted realtime stream of images spied on one of his screens as the base of the ladder.

[more…]